Humans versus technology (and governments): Occupy EU

November 8, 2011 3 Comments

I am so happy that I am not alone in my take on the Paradiso Conference, although the Conference itself is not mentioned. Not only has an Open Letter been written to the European Commissioner for Research and Innovation (Máire Geoghegan-Quinn), but, to date, over 10,000 people from across Europe have signed it.

This letter, which you can view at http://www.eash.eu/openletter2011/index.php?file=openletter.htm , is entitled “Horizon 2020: Social Sciences and Humanities research provides vital insights for the future of Europe”.

The letter points out what Blind Freddy can see: that European society is complex and diverse, and it is more appropriate to talk about ‘societies’ and ‘cultures’ in the plural, rather than the singular. This in turn suggests that there is no ‘One size fits all’ strategic plan, economic model or financial solution that can possibly be the most appropriate for all the countries in Europe, particularly those who are already members of the European Union. The ongoing financial crisis in Greece (which is largely about banks not losing money, rather than austerity or poverty experienced by the people of Greece) has provided a very clear example of this.

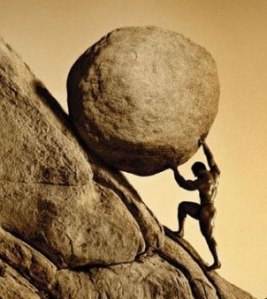

This letter encourages creative responses to the question of what Europe will look like in the future, given current (and historical) events. While there is little doubt that there will be change and transitions, as is pointed out, in the final analysis it is the people – of Europe and elsewhere in the world – that should be the focus of all debate, and their well-being the goal to be achieved. I sometimes think that ‘strategy planners’ forget such simple facts, and assume that’s what is good for them (their companies or banks or governments or whatever) will somehow, by default, be good for the population at large. We know this is untrue, as we see corporations scurrying to make profits for their shareholders (some of whom are us!) rather than considering the environment or any other short or long term ethical issue.

As far as academia is concerned, and the information professions in particular, this letter raises important issues. For example, multidisciplinary and interdisciplinary work is encouraged in order to deal with the complex problems that we face: none of the ‘disciplines’ – whatever they are – has the vision, knowledge, methodologies or skills to imagine and put into place suitable solutions on its own.

In particular, it seems to be generally forgotten that ‘change’, whenever it is mentioned, is only important to us if societal change will occur – as a stimulus or a response to, for example, changing medical practices or changing technologies. We are only interested in change, for the most part, if it will affect our lives in some way: our work, the education of our children, or where we will take our holidays. If changes occur within a praxis (for example, new techniques for hip replacements) we would only be interested if, for example, either we or somebody we knew were to undergo such a procedure.

Those who praise technology as the most important, or perhaps even the only, agent of change have sadly completely misunderstood what the question was: particularly those who are designing technologies for problems or events that don’t yet exist, where they hope the technology will bring such phenomena or entities into existence. And this is not to say that this doesn’t happen – look at the internet generally, and Google and Facebook in particular. But I am fairly certain that none of those involved with the development of these had any idea how they might be used and, indeed, are used quite differently from what they may have imagined.

As the Open Letter points out, we cannot let the future be determined solely by the technologists: a number of challenges (and perhaps the most important ones) fall well within the bailiwick of the Social Sciences and Humanities (SSH). And that, fellow information professionals, means us. These areas include, as noted in the Letter, education, gender, identity, intercultural dialogue, media, security, and social innovation (to name but a few). The Letter notes that it is the “key behavioural changes and cultural developments” which should concern us: “changing mindsets and lifestyles, models for resilient and adaptive institutions” are mentioned as examples. The authors call this challenge “Understanding Europe…” and believe it is as important as other challenges such as food and transport. They state, “a climate of sustainable and inclusive innovation in Europe can only be established, if European societies are conscious of their opportunities and constraints – this knowledge is generated by Social Sciences and Humanities research”.

It is time, I think, for all information professionals to consider carefully, and to articulate, how they see their societal role. This is as important for the world as it is for individual professional futures.

Related articles

- European Researchers Night 2011 (electronics-lab.com)

- EU vs Facebook: Facebook’s dossiers on Europeans breach EU privacy laws (boingboing.net)

- EU is corrupt and beyond fixing – ex-UK minister (rt.com)

- Sense or nonsense of “Human Fragility” (marcusampe.wordpress.com)

- Europe. A democratic deficit. Or two. (cedarlounge.wordpress.com)

- Time is running out for Europe (tradingfloor.com)

- Africa – E.U High Level science, technology and innovation Policy dialogue platform (appablog.wordpress.com)

- The Grand Plan for Europe became the Waterloo of the Eurozone (tradingfloor.com)

- New code tells European researchers how to behave (blogs.nature.com)

- Shaping new visions for EU-research in digital preservation (girlinthearchive.wordpress.com)

- Humanities researchers and digital technologies: Building infrastructures for a new age (eurekalert.org)